Table of Contents

In computer programming, a thread pool is a software design pattern for achieving concurrency of execution in a computer program. Often also called a replicated workers or worker-crew model, a thread pool maintains multiple threads waiting for tasks to be allocated for concurrent execution by the supervising program

-- Wikipedia

Repository: https://github.com/arindas/sangfroid

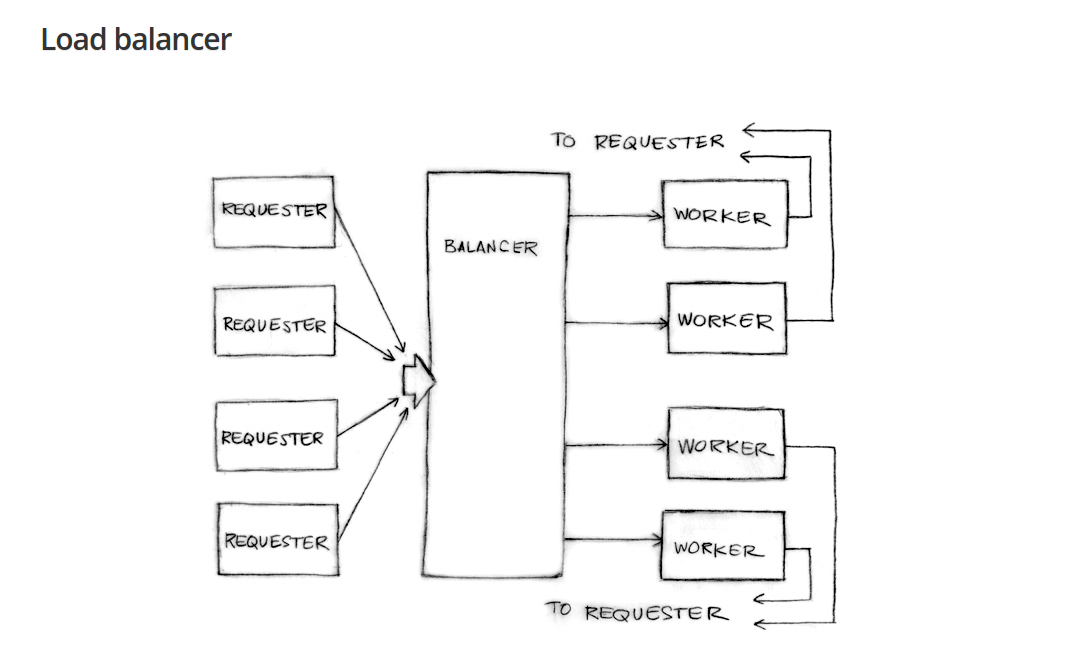

This endeavour was largely inspired by the load balancer from the talk "Concurrency is not parallelism" by Rob Pike.

Often it is useful to have a clear goal while encumbering upon a task. So what is our goal here? In the simplest sense, we want a system, which allows us to:

- Schedule some work to be done among multiple workers

- Be able to receive the result of the work done from the workers

- Ensure that the workers are sufficiently busy while also not suffering from burnout.

Notice how this kind of system is not directly tied to computers. A model like this can also be applied to any team of humans who have to accomplish some tasks.

So how do we go about modelling and solving this?

Let's say we have customers who need some work to be done. A manager which coordinates some employees, and the employees in an organisation. Here's one of the ways, work can be organised:

- The customer emails the manager what needs to be done by sending an email.

- The manager chooses the employee with the least amount of pending tasks and adds a new email in the same email chain, notifying that employee to take upon that task.

- The employee chooses the tasks from all the emails he received from his manager. Once he is done with a task, he attaches the result of the work in the same email chain and replies to the customer.

- The manager keeps note that the employee has one less task to work on.

Notice that, once the manager assigns the employee to a particular task, the customer and the employee are directly connected. The manager need not be responsible for relaying back the result of the work from the employee to the customer. This is one of the properties that we would be highly appreciable to the manager.

How does this tie into software systems you ask?

The customers can be clients who send web requests to a server. The manager is the webserver. And the workers are lightweight processes or threads. The webserver schedules web requests among the threads working which directly respond to the client with the response. With this, you have a web serving architecture.

Now, it is not feasible to keep on creating new threads with every single request, since each thread requires some memory, and involves some time for context switch from one thread to another. However, with this model, we can scale with a fixed number of threads.

Still, we haven't solved a part of the problem. How do we efficiently pick up the least loaded worker every time?

Each worker maintains a list of pending tasks it needs to solve. We then maintain a binary heap of workers, based on the lengths of their lists of pending tasks. We update this heap whenever a worker receives a new task or finishes a task.

Well, that was enough talk. Let's see some code!

A dynamically prioritizable priority queue

That sounds a bit heavy, doesn't it?

We simply mean that we need a priority queue, where the ordering of the elements we will be using can change at runtime. Just like how our workers are prioritized for new tasks based on the number of pending tasks they have, at any given moment.

The code for this section can be found at: https://github.com/arindas/bheap

Let's begin!

We model our heap as follows:

/// Trait to uniquely identify elements in bheap.

/// A re-prioritizable binary max heap containing a buffer for storing elements

/// and a hashmap index for keeping track of element positions.

This binary heap is generic over all types that are orderable and can be identified uniquely. (Traits are mostly similar to interfaces in other languages. Read more here.)

We use a vector as our underlying storage for the binary heap. Since our elements can be dynamically ordered, we need a mechanism for keeping track of their identity and maintaining their indices.

This is what the swap( ) function looks like:

It was necessary to borrow self.index as mut separately since it would otherwise require us to borrow self as mut more than once in the same scope.

Here's heapify_up():

/// Restores heap property by moving the element in the given index

/// upwards along it's parents to the root, until it has no parents

/// or it is <= to its parents.

/// Returns Some(i) where i is the new index, None if no swaps were

/// necessary.

There's nothing special about heapify_dn() too. You can check it out in the repo. The only important thing to notice is that we use the swap_elems_at_indices() function every time.

Finally, our "dynamic prioritization" is here:

// ...

/// Restores heap property at the given position.

/// Returns the position for element in the heap buffer.

} // BinaryMaxHeap

Now that we have the container for workers out of the way, let's implement the actual thread pool.

The load-balanced thread-pool

Code for this section can be found at: https://github.com/arindas/sangfroid

Supporting entities

First, we need to define what a task or a Job is:

/// Represents a job to be submitted to the thread pool.

The Send trait boundary is necessary for types that can be moved between threads. In our case, we need the result to be sendable from the worker thread to the receiver right? Hence it's necessary.

Now let's go over the members in detail:

taskrepresent a closure that can contain some mutable state. Since its return value needs to outlive its scope, its return type is marked with'staticlifetime, meaning its result will be alive for the entire duration of the program. It's alsoSendable. (As explained above)req: represent the parameter for the taskresult_sink: The sending end of the channel from which the requester can receive the result.

Hmmm, the last part seems a bit involved, doesn't it?

Whenever we create a Job we create a channel for communicating with the worker. Think of the channel as a pipe that has a sending end and a receiving end. Now the requester keeps the receiving end while the Job struct contains the sending end. When the Job is scheduled, the ThreadPool gives the job to the least loaded worker thread. The worker thread runs the closure inside the Job and sends back the result computed, into the sending end present in the Job struct. This way the worker thread was directly able to communicate the result with the requester.

Notice how the above approach, didn't require any synchronization on libraries or user's end for communicating the result. Here we share the result (or memory) by communicating, instead of communicating by synchronizing (or sharing memory) in some data structure. This is precisely what we mean when we say:

Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

The rust standard library provides channels with std::sync::mpsc::{channel, Receiver, Sender}. Channels are created like:

let = ;

For instance, a Job is constructed as follows:

Now we need a unit of communication with the worker threads. Like so:

/// Message represents a message to be sent to workers

/// in a thread pool.

Worker threads

The worker threads are represented as follows:

/// Worker represents a worker thread capable of receiving and servicing jobs.

We have simple setters for incrementing and decrementing worker load:

/// Increments pending tasks by 1.

/// Decrements pending tasks by 1.

Now at the time of the creation of workers, we create a channel for dispatching messages to the worker. The sending end is part of the struct and is used by the worker manager, while the receiving end is uniquely owned by the thread servicing the jobs.

The core of the worker thread is simply a while loop where we continuously receive messages from jobs source until no further jobs are available. For every job, we respond with the result and notify completion of a task.

Jobs may be dispatched to the thread as follows:

/// Dispatches a job to this worker for execution.

Finally, we terminate a worker thread by sending a Terminate message to it and join()-ing it.

/// Terminates this worker by sending a Terminate message to the underlying

/// worker thread and the invoking join() on it.

// ...

} // Worker

ThreadPool

We represent the thread pool as follows:

/// ThreadPool to keep track of worker threads, dynamically dispatch

/// jobs in a load-balanced manner, and distribute the load evenly.

Let's go over the members :

pool: The data structure for containing our workers. We wrap it with a mutex since we use it both from the ThreadPool struct members and from the balancer thread. TheArcis necessary for making itSend-able.done_channel: The sending end of the channel to notify that a worker with a given uid has completed a task, by sending the uid of the worker in question.balancer: The balancer thread responsible for restoring the heap property once a worker completes a task.

The workers are created as follows:

/// Creates the given number of workers and returns them in a vector along with the

/// ends of the done channel. The workers send their Uid to the sending end of the done

/// channel to signify completion of a job. The balancer thread receives on the

/// receiving end of the done channel for Uid(s) and balances them accordingly.

///

/// One of the key decisions behind this library is that we move channels where they

/// are to be used instead of sharing them with a lock. The sending end of the channel

/// is cloned and passed to each of the workers. The receiver end returned is meant

/// to be moved to the balancer thread's closure.

The balancer thread is created as follows:

/// Returns a `JoinHandle` to a balancer thread for the given worker pool. The balancer

/// listens on the given done receiver channel to receive Uids of workers who have

/// finished their job and need to get their load decremented.

/// The core loop of the balancer may be described as follows in pseudocode:

///

/// while uid = done_channel.recv() {

/// restore_worrker_pool_order(worker_pool, uid)

/// }

///

/// Since the worker pool is shared with the main thread for dispatching jobs, we need

/// to wrap it in a Mutex.

The logic for restoring the heap property after decrementing a workers load is as follows:

/// Restores the order of the workers in the worker pool after any modifications to the

/// number of pending tasks they have.

Hence, we create a ThreadPool with worker threads and a balancer thread as follows:

Next, we need to be able to dispatch Jobs to this thread pool. The idea is simple, pop the head of the heap, update its load and restore it in its correct position.

/// Schedules a new job to the given worker pool by picking up the least

/// loaded worker and dispatching the job to it.

This is how it is used by the ThreadPool struct:

As said before, locking on the worker pool is necessary since we share it with the balancer thread.

Finally, we need a mechanism for terminating all threads in the binary heap of workers:

/// Terminates all workers in the given pool of workers by popping them

/// out and invoking `Worker::terminate()` on each of them.

We use the above function in the ThreadPool::terminate(). Here it is necessary to terminate both the worker pool and the balancer thread.

Remember that we wrapped the pool in an Option? It was so that we could move it to the current scope when deallocating.

We also invoke terminate() on drop():

This concludes our implementation of the thread pool.

Go through the tests for ThreadPool here.